Episode Two: All the Pope’s Men

In the first episode, we left Riccardo Galeazzi on the threshold of history: an eye doctor with a gambler’s pulse, a man who would one day become inseparable from Eugenio Pacelli — who was not yet Pope Pius XII — and then infamous for a funeral catastrophe the Vatican would prefer to forget.

There is, however, a quieter prelude to scandal: the question of how these two men met. The folklore is abundant; the documents are stubborn. What follows are four competing versions — each plausible, each compromised.

Version One: The Speck of Dust

On June 28, 1930, cardinal Pacelli walks up Via Sistina and feels a sting in his eye.

He glances around, sees an oversized sign — STUDIO OCULISTICO RICCARDO GALEAZZI — and steps inside.

It’s irresistible as an anecdote (chance as destiny), but Galeazzi himself later warns against it in his memoir In the Shadow and the Light of Pius XII: great churchmen do not entrust their bodies, let alone their eyes, to a stranger on a whim.

The sign of Galeazzi’s practice, seen in an AI-restored image that in fact depicts the sign at a later time — most likely in the 1950s — by which time Galeazzi had long since added the second surname, Lisi.

Page from Riccardo’s book containing the passage: ‘It has been said that, happening to pass along Via Sistina, Eugenio Pacelli had seen my plaque and wanted to come up to have his eyes examined. Nothing could be more fanciful! An ecclesiastical personality never goes “by chance” to a doctor’s office; he chooses carefully and always has himself announced.’

The page also includes a rebuttal of the second version — that Pacelli had gone to get eyeglasses.

Version Two: The Spectacles

Pacelli came for eyeglasses. Except Galeazzi never sold them.

This is written by Galeazzi himself in his autobiography, and corroborated by a journalist who spent time in the practice as children, Bruno Bartoloni, who remembered a large, sparsely populated room, the Snellen chart, the instruments, and not a single display case of frames.

Riccardo was a clinician, not a shopkeeper.

Version Three: The Duchess

Monsignor Quirino Paganuzzi later claimed that a society grandee — the Irish-American philanthropist Genevieve Garvan Brady — recommended Galeazzi to Pacelli.

Perhaps. The 1930s Vatican was not short on cultivated women with access; still, it is difficult to picture a punctilious, old-world prelate like Pacelli entrusting his private medical concerns to a salon…

What is certain is that on June 28, 1930, at 4 Via Sistina, the two men met — and neither forgot the other.

Galeazzi admits as much: “The nobility of his face and the sweetness of his voice… enrolled me among his admirers at once.”

Soon, Galeazzi was no longer merely an ophthalmologist. He had become what he would remain for nearly three decades: the cardinal’s (and later the pope’s) physician of first resort.

A Doctor, a Psychologist, a Priest

In 1932, Riccardo Galeazzi founded the Roman Homeopathic Center in his own practice on Via Sistina and invited the eminent Dr. Antonio Negro to join its board.

In the archives of the Museo dell’Omeopatia on Piazza Navona, the paperwork still breathes under glass.

On January 9, 1938, the Roman Homeopathic Center held its first assembly at Palazzo Capizzucchi in Piazza Campitelli.

During the afternoon session, members passed a “vote of confidence and praise in favor of Prof. Dr. Galeazzi Lisi,” their founder — a record preserved today in the Museum of Homeopathy at Piazza Navona.

Later that same year, as reported by L’Illustrazione Italiana on September 11, 1938, Galeazzi-Lisi represented Italy at the International Congress of Homeopathy in Nice, where his presentation on a new method of drug absorption earned wide applause.

Plans were laid to host a world congress of homeopathy in Rome in 1942, coinciding with the planned Esposizione Universale—an event that, of course, never took place due to the war.

What did “homeopathy” mean in this milieu?

A method that insisted on lentezza: the slow, exhaustive anamnesis of a person as a person.

The homeopathic physician, Antonio Negro liked to say (his son repeats the formula with undimmed conviction), is at once doctor, psychologist, and priest.

He observes preferences, dreams, the hour at which pain bites. He looks for the seam where body and story have frayed.

Does that aura of total care explain Pacelli’s choice of an eye specialist as personal physician?

Partly.

A patient whose ailments ranged from gastritis to arrhythmia, chronic hiccups to dislocating joints, low blood pressure to a creeping arthritis that would stiffen his right arm — such a man has reasons to value a listener who treats every complaint as a thread in one tapestry.

Galeazzi offered exactly that: a unity of attention. Whether you call the drops and pellets medicine or metaphor, he produced the result that matters most to a patient in high office — relief reliably delivered by a trusted hand.

It is not manipulation to say so. It is fidelity to the record.

Honors and Allegiances

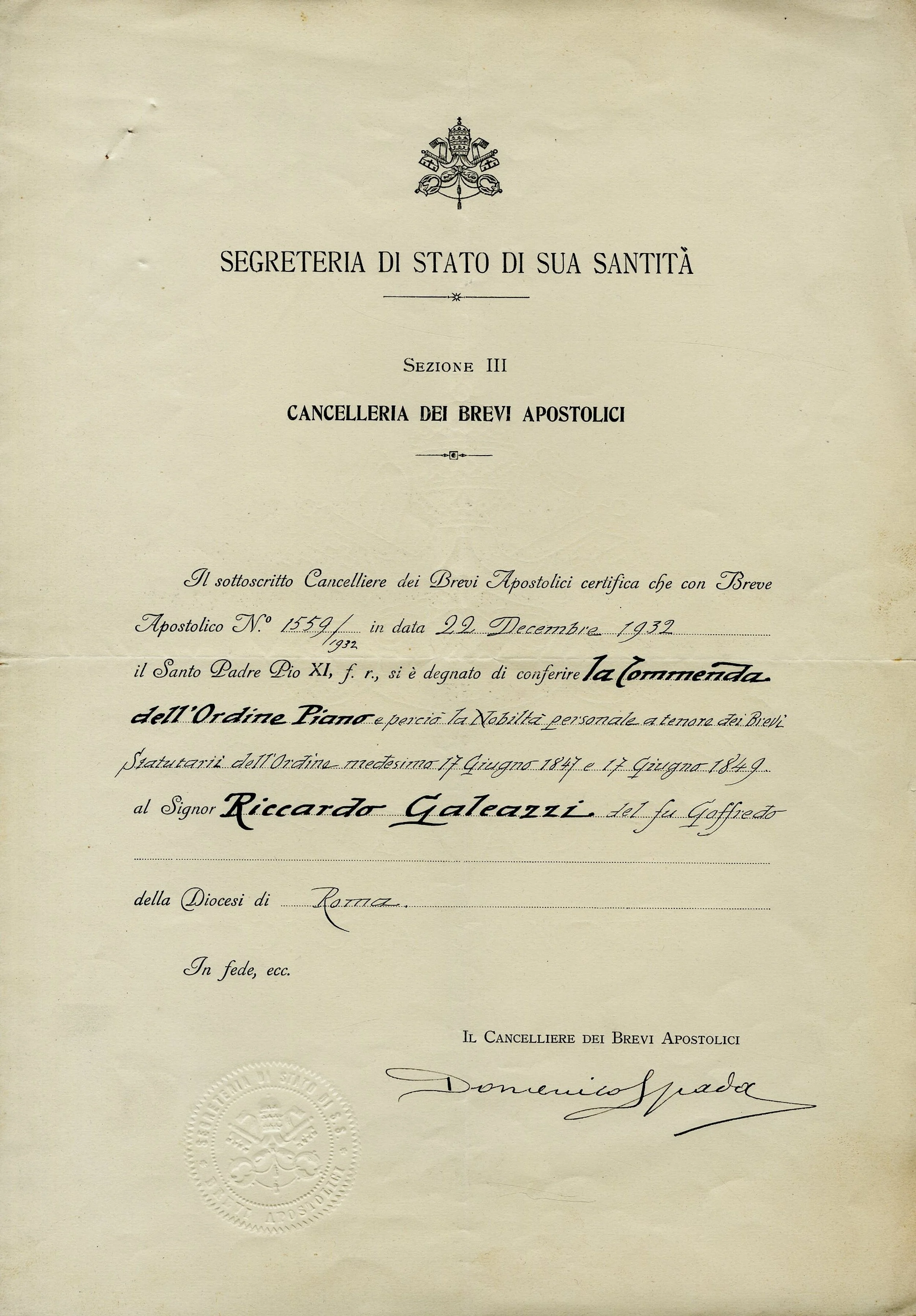

As documented in his Fascicolo Araldico — the file preserved in the Italian State Heraldic Archives and displayed here — Riccardo Galeazzi received the title of Commendatore dell’Ordine Piano (Commander of the Order of Pius) on December 22, 1932, in a papal brief issued under Pope Pius XI and personally written and signed by Cardinal Eugenio Pacelli, the future Pius XII.

It is evident that this distinction was born of the profound esteem that Cardinal Pacelli — by then his patient and confidant — had come to hold for his personal physician.

The brief is, in fact, tangible proof of a relationship that had grown far beyond the formal boundaries of medicine: an alliance of trust, admiration, and intellectual intimacy between a prelate of rare discretion and a doctor who, more than most, seemed to understand both the fragility and the majesty of the human soul.

King Victor Emmanuel III of Italy authorized him to wear the insignia of this papal order within the Kingdom of Italy and its colonies.

Excerpt from the royal decree by which King Victor Emmanuel III authorizes Riccardo Galeazzi to bear in Italy his Vatican noble title, entrusting “the Duce of Fascism, Head of Government,” Benito Mussolini, with the administrative execution of this order. The document bears the King’s own handwritten signature.

On July 31, 1933, Riccardo Galeazzi formally joined the National Fascist Party, a move that by then had become virtually compulsory in Italy, especially for anyone involved in dealings with government offices, public institutions or the Vatican.

Excerpt from a report by the Chief of Staff of the Office of the Italian Prime Minister, stating: “Grand Officer Dr. Riccardo Galeazzi [...] born in Rome on July 26, 1891, and residing at 142 Corso Trieste, maintains an irreproachable conduct in every respect: he is married and has children; he professes the Catholic religion and has been enrolled in the National Fascist Party since July 31, 1933.”