Episode One: The Devil’s Hour

The body of Pope Francis lies in state (Associated Press photo)

On April 21, 2025, at 7:35 in the morning, Pope Francis died suddenly. For three days, thousands of mourners filed silently past his body, displayed in Saint Peter’s Basilica at the heart of the Vatican.

Behind the solemn ritual lies a hidden science: thanatopraxis. As Nicoletta Orlandi Posti explained in an April 24, 2025 article in Libero, “thanatopraxis is the post-mortem procedure that allows for the temporary preservation of the body, repeated after the death of every pope.”

The article also referred to tragic events that took place in 1958.

The horror of 1958

In October 1958, Eugenio Pacelli, Pope Pius XII — the wartime pope, one of seven titans who clashed on the world stage alongside Churchill, Roosevelt, Stalin, Hitler, Mussolini, and Hirohito — died in the papal summer residence of Castel Gandolfo.

During his funeral, the unthinkable happened. His body, embalmed by crude methods, swelled grotesquely and then burst open before horrified witnesses.

The blame has always fallen on Riccardo Galeazzi Lisi, Pius XII’s personal physician.

An ophthalmologist by training, not an embalmer, he had devised a bizarre preservation technique: wrapping the pontiff in cellophane with herbs, on the grounds that Christ’s body too had been swathed in cloth with spices.

“Taking Jesus’ body, the two of them wrapped it, with the spices, in strips of linen. This was in accordance with Jewish burial customs.” (Gospel of John 19:40)

What followed was a disaster that scarred Vatican memory for decades. To prevent a repetition, the Vatican refined and institutionalized the science of papal thanatopraxis.

Pius XII’s body lying in state as Dr. Galeazzi Lisi checks his precarious condition. At left, a Palatine Guard.

The Doctor in the Shadows

Who was Dr. Riccardo Galeazzi Lisi?

He was a gambler who turned up in court cases, tabloid headlines, and even in connection with one of Italy’s most notorious unsolved mysteries, the Wilma Montesi murder.

He was accused of selling photographs of the dying pope to the press for money, and for that he was eventually expelled from the Vatican once and for all. He certainly helped spread premature reports of Pius XII’s death. He certainly experimented with pseudoscientific treatments.

And yet, none of this explains why Pius XII — a shrewd and formidable man, not easily deceived — chose him as his personal physician, trusted him, and kept him at his side for 30 years.

Why did the pope tolerate such a figure in his inner circle?

And how did Galeazzi Lisi manage to secure — and keep — the trust of the most powerful and controversial pontiff in modern history?

These unanswered questions make the standard caricature of Galeazzi Lisi impossible to sustain. They also cast an unexpected light back onto Eugenio Pacelli himself.

And these are the questions that drive this investigation.

A Prophecy and a Destiny

The story cannot be told without tracing the rise of Pius XII.

Eugenio Pacelli, born in Rome in 1876 to a devout Catholic family, seemed destined for the Church from childhood.

Many anecdotes surrounded his birth. One is recounted in Andrea Tornielli’s Pio XII. Eugenio Pacelli. Un uomo sul trono di Pietro (Tornielli, 2007).

A priest named Don Jacobacci is said to have stepped forward at Eugenio’s baptism, lifted the infant Pacelli high in his arms, and declared,

“Sixty-three years from today, Eugenio Pacelli will be pope!”

The story, however, did not appear until decades later, in a hagiographic pamphlet, and was almost certainly invented. Even so, it lent Pacelli’s life an enduring aura of destiny.

As a boy, Eugenio Pacelli dressed up as a priest and staged masses at home. He studied at the Liceo Classico Statale “Ennio Quirino Visconti”, a fashionable school in Rome that he later described as anticlerical and freemason in spirit.

There he wrote an early self-portrait, describing himself as mediocre in appearance, prone to impatience yet quick to forgive (Tornielli, 2007). Handwriting expert Evi Crotti, as cited in Tornielli (2007), identified in his handwriting an absolute control of aggressive impulses, deliberately suppressed at great personal cost, leading to psychosomatic symptoms.

Pacelli rose quickly. He became a priest at twenty-three, an expert in canon law, and then a gifted diplomat. In the nineteen twenties he became the Vatican’s leading envoy to Germany, negotiating concordats to protect Catholic minorities.

But his most fateful act came in 1933, when, as Secretary of State under Pius XI, he signed the Reichskonkordat with Hitler’s Germany. The photograph below shows the historic moment.

Cardinal Pacelli signs the Concordat with Reich officials. Photograph from the Lebendiges Museum Online, colorized by Palette.fm.

Defended at the time as a way to shield Catholics, it later became one of the most controversial agreements in Vatican history.

Six years later, when the cardinals gathered in conclave, they elected him pope. On March 3rd, 1939, Eugenio Pacelli became Pius XII, just as Europe slid into the abyss of war.

Within days of his election, a mystery surfaced in the Vatican.

A relatively unknown ophthalmologist, Dr. Riccardo Galeazzi Lisi, suddenly began appearing at the papal apartments. He had no official appointment, yet moved in and out with striking ease.

Cardinal Francesco Marmaggi, head of the powerful Congregazione del Concilio —effectively the Vatican’s “interior ministry” — summoned a physician for a discreet briefing.

“A well-known Roman physician was informed that Cardinal Marmaggi wished to speak with him; he would not, however, receive him in the Palace of the Congregations in Piazza San Callisto, but in his modest villa on the Janiculum Hill. Cardinal Marmaggi […] was then Prefect of the Sacred Congregation of the Council, meaning that he headed what is considered the Ministry of the Interior of the Church. From the Cardinal, a true-born Trastevere native, the physician was addressed in Roman dialect with an unexpected question: “Who exactly is this Professor Riccardo Galeazzi?” At that time the professor was called simply Galeazzi; the addition of the surname Lisi came later, following an inheritance. Cardinal Marmaggi explained plainly why he wished to be informed about Professor Galeazzi. He was seen not infrequently in the Vatican, in the papal apartment: always impassive, with that expressionless face. […] Since the second of March the oculist had in effect continued to be the Pope’s physician, though without having been formally appointed. […] The Pope intended to appoint Galeazzi as Pontifical Archiater. But did he have the qualifications to hold so lofty and so responsible a position? […] Yet the Roman physician, questioned that day, thought it appropriate to report to the prelate what was being said in Roman medical circles about the oculist Galeazzi, who even then had his practice at number 4 Via Sistina […]. It was a spacious, well-equipped modern practice, consisting of several rooms, and beneath the windows ran a large conspicuous sign, plainly an eyesore. Now that very sign, which was at the time quite a novelty in the Roman medical world, as well as the plaque on the doorway with the indications “Cataract operations – Corrections of myopia – Electrical treatments,” had provoked the intervention of the Medical Association, presided over by Dr. Lazé. He had met with his colleague Galeazzi and had called his attention to that sign and those inscriptions, which had aroused the criticism of Roman physicians. But Galeazzi had left the sign where it was. A second intervention, in the same year, was undertaken, again without any result, by the Italian Ophthalmological Society, then presided over by Senator Ovio. Furthermore, some Roman physicians disapproved of the way Professor Galeazzi flaunted the therapeutic virtues, in matters of eye diseases, of a lotion he called “of the friar of Bergamo.” No matter how much research was done, nothing was ever discovered about that friar. But this remark may also have been the product of the possible jealousy of certain professionals toward their more fortunate colleague, who had a splendid practice in the heart of Rome and was beginning to count on a numerous clientele. […] Cardinal Marmaggi, who had received the same information from other physicians as well, hinted that there was nothing to be done. Professor Galeazzi would be appointed Archiater by the Pope, and his name would officially appear among the members of the pontifical household. This is exactly what happened the following year.”

(article by Rocco Morabito)

The Devil’s Hour

Who was Riccardo Galeazzi Lisi?

To understand, one must go back to his origins.

Birth Certificate of Riccardo Galeazzi Lisi

Riccardo Arturo Domenico Filippo Maria Galeazzi was born in Rome at 3:10 a.m. on July 26, 1891, ten minutes after what Italian folklore called the Devil’s Hour, a sinister inversion of Christ’s death at 3 p.m.

His childhood was marked by trauma. In December 1900, his beloved older sister Virginia died suddenly at age 15.

Death Certificate of Virginia Galeazzi, aged fifteen, daughter of Goffredo Galeazzi and Emma Lisi, who were also the parents of Riccardo

Riccardo, then nine, experienced a temporary decline in his eyesight. An ophthalmologist’s care inspired his future vocation.

As a young man Riccardo studied medicine and served as an army doctor in the First World War. The horrors of the front haunted him. Back in Rome, he looked for adrenaline wherever he could find it: at poker tables and behind the wheel of racing cars. Under the pseudonym “Maometto” (Muhammad), he raced Maseratis and lived recklessly, gambling away fortunes and winning them back in single nights.

In the photo, a relatively young Riccardo Galeazzi Lisi is at the wheel of a Maserati Tipo V4 16 cylinder. A legendary car of incalculable value. Designed to dominate the second Monza Grand Prix of September 15, 1929, Riccardo’s V4 was the first car to be fitted with two Grand Prix engines and two prototype carburetors crafted by Edoardo Weber himself to keep them in balance. Powered by an experimental mixture of gasoline, benzole, and ether, this car could reach speeds of 260 kilometers per hour. Driven by Baconin Borzacchini, it set Maserati’s first-ever world record — with a staggering average of 246 kilometers per hour — finished third at Monza and at the sixth Coppa Acerbo, and won the sixth Tripoli Grand Prix.

Page from Riccardo’s file at the Ministry of the Interior, Directorate-General for Public Security. The note is dated October 28, 1958, and records, among other things, that “the former Archiater has a passion for gambling and is said to have repeatedly lost substantial sums in Monte Carlo.”

Charlatans and Miracles

In 1929, Rome buzzed with the arrival of Fernando Asuero, a Basque doctor hailed as el doctor milagroso. At the Grand Hotel Excelsior on Via Veneto, the wealthy and the desperate flocked to his bizarre nasal “trigeminal therapy,” said to cure everything from sciatica to Parkinson’s. Newspapers alternated between ridicule and sensationalism. Patients swore by him, others denounced him as a fraud.

This image, from the archives of Dr. Fernando Asuero, is said to show the before-and-after of a miraculous cure performed on a member of the Guardia Civil. It appears in the scientific article “Las curaciones prodigiosas del doctor Asuero: trastornos neurológicos psicogénicos en la población española” by Dr. S. Giménez-Roldán, published in Neurosciences and History, 2015; 3(2): 49–60.

An Italian disciple, Benedetto Vincenzini, promoted his own variant — “nasal reflex therapy” — using cocaine for anesthesia.

Promotional booklet for Dr. Benedetto Vincenzini’s treatments.

The text includes the phrase: “the minor operation is entirely without risk, bloodless, and absolutely painless, because it is carried out, especially in certain cases, after complete anesthesia of the nasal mucosa with cocaine.”

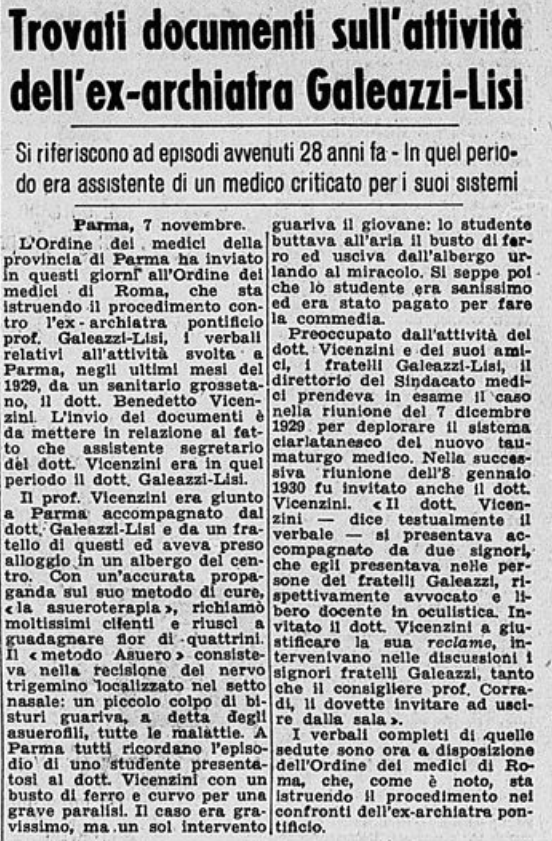

When Vincenzini faced trial in Parma that December, two brothers appeared at his side: Giulio Galeazzi, a lawyer, and Riccardo, the oculist. They tried to defend him before the medical board. Both were expelled from the hearing.

Riccardo would later deny any involvement with Asuero. Yet his presence at Vincenzini’s side, and his defense of questionable therapies, fed suspicions of charlatanism that followed him throughout his career.

Article from La Stampa reporting on the ties between brothers Giulio and Riccardo Galeazzi and physician Benedetto Vincenzini, during the disciplinary proceedings against him in Parma.